The Malaria Epidemic Through the Ages

In this post I’ll be participating in TidyTuesday, a weekly event where you’re challenged to analyze a new dataset. This week’s dataset is on malaria- a parasitic illness that is spread by mosquito bites. In 2018 there were approximately 228 million cases of malaria worldwide, leading to an estimated 405,000 deaths. Better understanding the incidence of malaria and its associated patient demographics could allow for better prevention of the disease.

The data I’ll be analyzing consists of three different datasets: one on the malarial death rate per 100k people, one on the number of deaths by age group, and one on the rate of malaria cases per 1000 at-risk individuals. Each dataset has observations for each country over the course of varying time frames. Let’s begin by reading in the data.

# Read in data

mal_age = pd.read_csv('malaria_deaths_age.csv')

mal_death = pd.read_csv('malaria_deaths.txt')

mal_gen = pd.read_csv('malaria_inc.csv')

It looks like some of the column names are a bit long- let’s rename them. It also appears that there is an entry for world for each year of observations. I don’t plan on using this field, so I’m going to remove it.

# Rename Columns

mal_death = mal_death.rename(columns = {'Deaths - Malaria - Sex: Both - Age: Age-standardized (Rate) (per 100,000 people)': 'Malaria Deaths per 100k'})

mal_gen = mal_gen.rename(columns = {'Incidence of malaria (per 1,000 population at risk) (per 1,000 population at risk)' : 'Malaria Cases Per 1000 at Risk'})

# Drop world from entity list for each dataset

mal_age = mal_age[mal_age['entity'] != 'World']

mal_death = mal_death[mal_death['Entity'] != 'World']

mal_gen = mal_gen[mal_gen['Entity'] != 'World']

Now that we’ve cleaned up our data, let’s see how the rates of deaths due to malaria have changed over time.

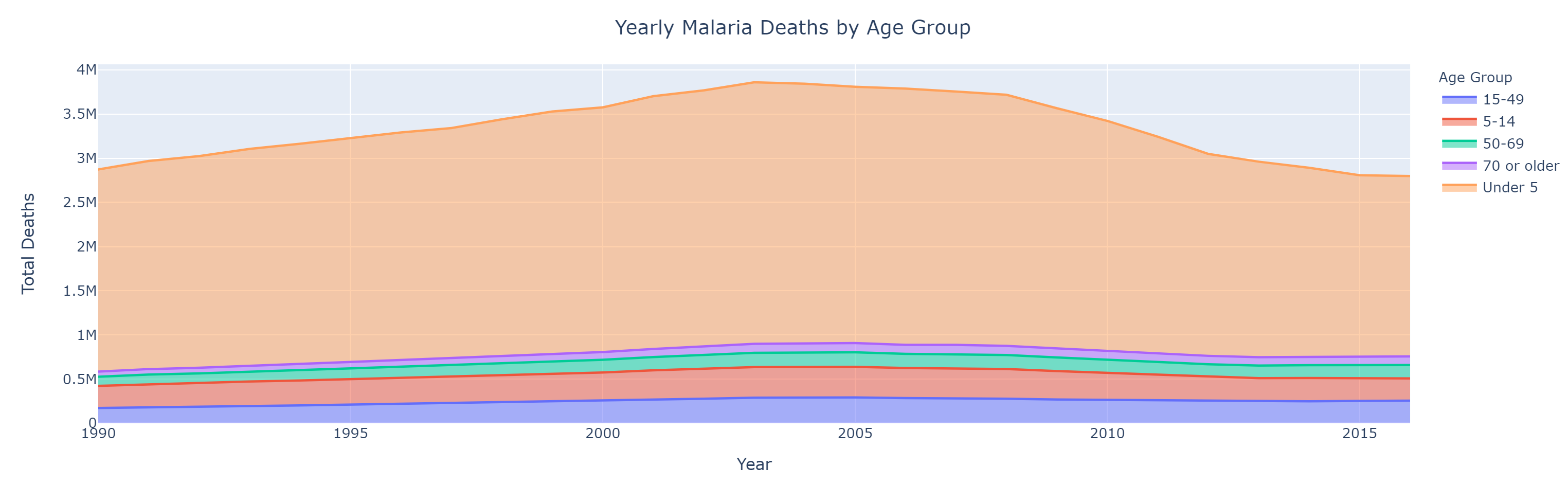

It appears that Africa has been the country hardest-hit by malaria. However, the rate of deaths has dropped in recent years. It may be that social or demographic changes are driving the change in overall deaths; let’s examine trends in deaths by age group to see if this is true.

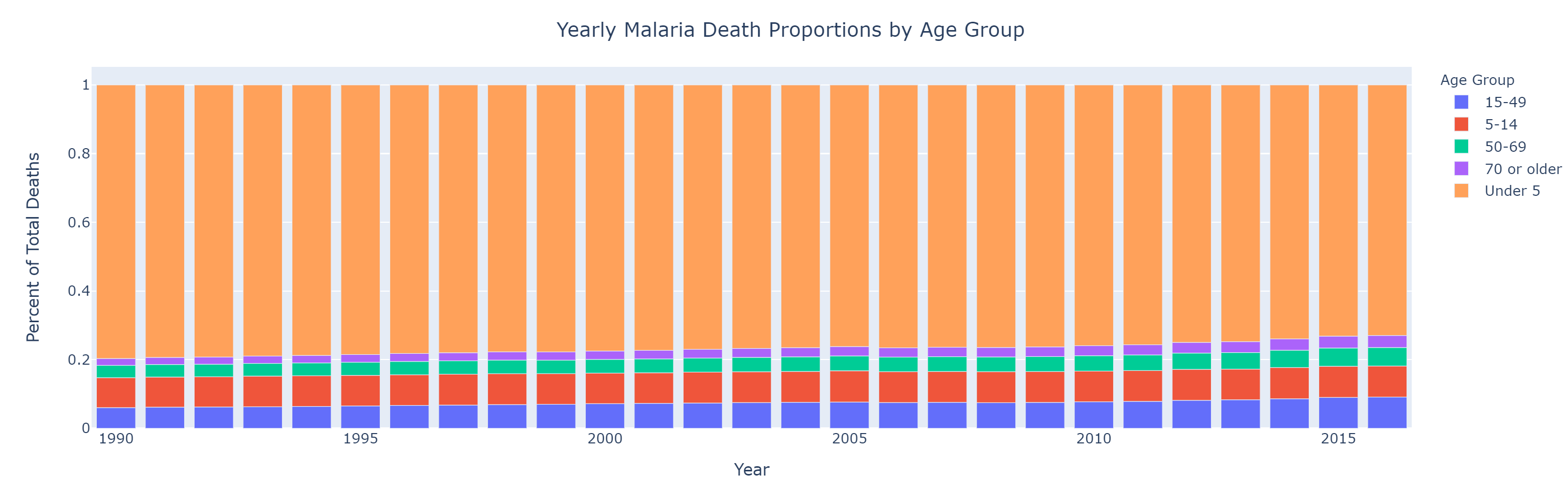

This graph allows one to see broad overall trends in deaths by age group, but it’s hard to accurately estimate the exact proportion of deaths in each age group. Let’s try looking at a chart that uses percentages rather than absolute numbers.

The breakdown of who dies of malaria is constant across years. Children under the age of 5 are the majority of those who die from malaria, followed by people ages 5-14 and 50-69. It’s interesting that the disease doesn’t seem to kill many elderly people. It may be that people who are already elderly are likely to have some form of malarial immunity that allowed them to survive to old age. This could be a genetic mutation, like sickle-cell anemia, or perhaps acquired immunity after a prior malarial attack.

What’s the relationship between cases and deaths?

Another interesting question is if the relationship between the incidence of malaria (measured as cases per 1000 at-risk) and deaths (measured as deaths per 100k people) has changed over time. Such a change could indicate that the quality of medical care in areas where malaria is endemic is getting better. Below is an interactive plot that shows death rate and malaria incidence for various time periods.

There seems to be a linear relationship between the case rate and the death rate overall. This makes perfect sense - the correlation between the two seems obvious. However, when you break it down by year, you can see that this relationship between the variables changes. Every year but 2000 seems to have a linear pattern. That year exhibits an almost exponential relationship; it may be that large numbers of cases overwhelm the health system, thereby causing the number of deaths to disproportionately increase. It would be interesting to examine what was happening in 2000 to find the ultimate cause.

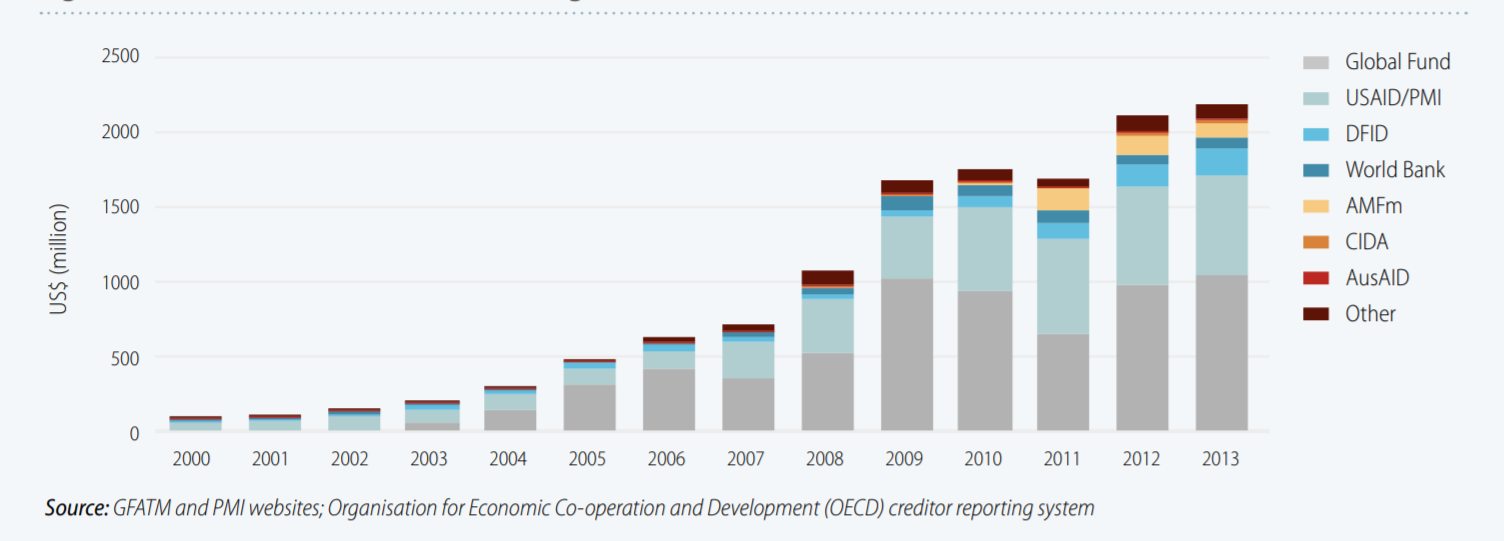

The question of why the death rate has decreased relative to the case rate can be explained by a variety of factors. In 2015, UNICEF published a study outlining the progress that’s been made in controlling the spread of malaria. Broadly, the amount of funding and resources available to combat malaria has increased each year.

This increase in funding has lead to an increase in accesss to vitally needed supplies, such as nets and medication, as well as an increase in public awareness about the disease itself. Below you can see that the proportion of feverish children being treated with ACTs (artemisinin-based combination therapies, a more effective malaria treatment) has been growing- this improvement in treatment may have helped lead to a reduced death rate.

Additionally, more people than ever now have access to insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs). Massive campaigns have been conducted to distribute nets and promote their usage all across sub-Saharan Africa. The results of these campaigns have been impressive; the proportion of children sleeping under a treated net has gone from almost 0 to over 60%.

The work to stop the spread of malaria, however, is not done. As the UNICEF report noted,

“Millions of people at risk of malaria still do not have access to an ITN, IRS, malaria diagnostic testing or ACTs. Access to these life-saving interventions is lowest among those living in the poorest households. Strategies that enable malaria interventions to be accessed by the poorest households (e.g. free distribution of ITNs and access to community-based treatment) will continue to be important in continuing to drive malaria down.”